Tom Parkinson, a long term Resident of Sanctuary Lakes Resort, provided a monthly column that offered a captivating exploration of the diverse range of flora and fauna thriving at Sanctuary Lakes.

Each month, he would take readers on a journey through the ever-changing landscape, highlighting the unique plant species and wildlife that call the area home. From the vibrant blossoms of native wildflowers to the diverse birdlife that nest in the surrounding wetlands, Tom provided insightful commentary on the natural beauty of Sanctuary Lakes, offering tips on how to appreciate and protect this rich ecosystem.

His column not only serveed as a celebration of local biodiversity but also as an educational resource for those interested in learning more about the flora and fauna that flourish in this tranquil environment.

To view past monthly columns, please click on the next page below or access your Residents App Kindred or the Web Portal (via the Member Login button), and under the Concierge section, go to Documents / Publications / Natures Rubik.

As I wander the estate there is a plant family that’s always there and without doubt, the most prodigious and well-maintained plants in Sanctuary Lakes. Yet after over 90 editions of Nature Rubik, I have never once mentioned them, either by their family or individual name. Those plants are of course, members of the Grass Family (Poaceae or gramineae).

Besides being a totally intricate part of our Estate’s streets, boulevards and parks, on a wider scale the Grass Family is undoubtedly the most important plant family to all mankind, agriculturally, economically and ecologically. It provides the major cereal crops and most of the grazing for wild and domestic herbivores. Grasslands alone are estimated to comprise about 20% of the world's vegetation. It is also one of the largest families of flowering plants. Other members of the Grass Family are used in Building materials such as Bamboo, Thatch and Straw. And for the really esoteric, one of its family provide the reeds for orchestral woodwinds, clarinets and saxophones.

All members of the Grass Family have similar basic structures. All Grasses have stems that are hollow except at the nodes. They have narrow alternate leaves borne in two ranks. The lower part of each leaf encloses the stem, forming a leaf-sheath. The leaf grows from the base of the blade, an adaptation allowing it to cope with frequent mowing and grazing. For the more technically minded, all grasses germinate as a monocotyledon.

There are two major methods of reproduction in grasses. Some grasses have additional stems that grow sideways, either below ground or just above it. Stems that creep along the ground are called stolons, and stems that grow below ground are called rhizomes. Grasses use stolons and rhizomes to reach out and establish fresh Grass zones. The stolon or rhizome nurtures the new plant until it is strong enough to survive on its own. The second method is by Flowers and seeds. In some grasses such as corn or maize, the flowers and seed are large and obvious, but small grasses also have tiny florets which will produce spores that in turn pollinate other florets to produce seeds. Unfortunately, in lawn grasses, the long thin leaves overshadow the other elements of the plant. Unless you're up close, all you see are green stalks.

What is the Grass Family History and in particular how did grass through gardens, parks and social play areas become an essential element to Human life?

Capability Brown designed Chatsworth Gardens

In medieval Europe the first known grass paddocks were grown surrounding the aristocracy’s grand mansions, castles and fortresses, allowing them to view from inside the safety of their walls, any approaching enemy, visitor, or villain.

In the early 18th century, landscape for the aristocracy entered a golden age, under the direction by one of England's greatest gardener Capability Brown, who refined the English landscape garden style with the use of Grass to design natural, and romantic, estate settings for the wealthy. Brown, designed over 170 parks, including Blenheim Palace, Warwick Castle and Kew Gardens, all of which still endure.

Australia at the turn of the twentieth century made its own use of grasses by the establishment of the so-called "nature strip" (a uniquely Australian term) and by the 1920s they had become an essential element throughout the developing suburbs of Australia.

The original landscaper of Sanctuary Lakes Estate Barry Murphy selected two main grasses for our Boulevards, Parks and Nature Strips, the Couch and Kikuyu, with a third Tall Fescue, to be used occasionally where needed.

Common Couch Cynodon dactylon

Couch is a warm-season grass that is known for its drought and softness underfoot, rich blue-green colour and water efficiency. It is a rhizome with a fine leaf blade that produces dense growth, it thrives in full sun areas and also has very strong horizontal growth. This allows it to tolerate very low mowing heights. These strong growth habits also attribute to its ability to handle high amounts of traffic, whilst enabling it to recover quicker if affected by wear and stress. This makes Couch turf suitable for large areas such as our parks, recreational areas, the Boulevard’s nature and median strips. One of Couch’s most favoured features is its natural dark blue-green colour and ability to maintain a strong colour even in poorer quality soils, although it can be subject to browning in cold winter climes. There are many different couch cultivars, the most common one being Santa Anna which is grown on the golf course.

Kikuyu Pennisetum clandestinum

The name Kikuyu comes from the East African tribe that lives in the region where the grass originates from. It’s wildly spread in Australia, New Zealand, and the southern region of California. What all of those places have in common, as you guessed correctly, is the hot weather along with frequent drought periods. Kikuyu grows via stolons and rhizomes. This means, the main quality of Kikuyu grass is that it thrives in such conditions, which makes it a popular choice among many gardeners and landscapers when planning organised cultivation of Parks, Playing Fields and Boulevards. The main visual difference between Kikuyu and Couch is their natural leaf size. Kikuyu has broad straight tall leaves that can reach up to 40 mm in length and 5 mm in width. It stands up tall in almost any weather conditions, even in the hottest days of the year, due to it’s strong, deep root base. This root system gives Kikuyu amazing regenerative powers that heal it quickly if damaged by say foot traffic. There’s also a negative, the strong root system allows Kikuyu to become very aggressive in expansion. If left on its own Kikuyu can very quickly become an obnoxious weed. It is the only member of the Grass Family to be banned from being planted within house lots by Sanctuary Lakes ARC committee.

Tall Fescue Festuca arundinacea

Tall Fescue is a perennial cool-weather turf grass that is used by gardeners because of its strong growth habits. The leaves are wide blades with a dark green colour that is maintained even in winter. The blades are very coarse to the touch, with topsides that are shiny. It is both drought and shade tolerant. They survive well without regular watering and grow in areas where it's too hot for cool grasses but too cold in the winter for warm-season grasses. Tall Fescue is a clumping type grass.

As I stated at the beginning, the Grass Family can be seen all around our Estate. The various leaf shapes and sizes, plus their green blue and even brown colouring makes the differences between the family species, relatively distinctive.

Commonly seen winging their way around our Estate are two different species of Birds that are often confused with one another and yet strangely, are extremely different. But yet again, they do have some similarities.

One, the Noisy Miner is a native Australian Bird, the other as the name suggests, is an introduced Asian Bird, the Indian Myna.

Noisy Miner (Manorina melanocephala)

Indian Myna (Acridotheres tristis)

They are from completely different bird species. The Noisy Minor hails from the Honeyeater family, while the Indian or Common Myna is a member of the Sturnidae/Starling family.

Although the body size and shape of the Indian Miner is similar to our own native Noisy Miner, that is where the main physical comparison ends.

The Noisy Miner body is a motley grey. Its wings are a slightly darker grey with yellow flecks and the under parts are whitish. Their beak and feet are a yellowy orange, they have a bright yellow triangular patch just behind their brown eye.

The Indian Mynahs head, neck, throat and wings are chocolate brown with a light green sheen. Their bill and legs are a bright yellow, also there is a white patch on the outer primaries and the underside wing linings.

But what adds to the visual confusion is that large distinctive bare yellow patch behind the eye of both the Noisy and the Indian. These yellow patches enlarge the eye giving the Birds a very aggressive appearance. An appearance that they take full advantage of.

Noisy Miners are without doubt gregarious and territorial; they forage, bathe, roost, breed and defend territory communally, the Noisy is a notably aggressive bird who seems to enjoy chasing, pecking, fighting, scolding, and mobbing throughout the day, targeting both intruders and even some fellow Miners.

The Noisy Miner loves our gardens and eucalyptus trees feedings on nectar, fruits and insects. Very occasionally they will eat small reptiles and amphibians. Food is either taken from trees or on the ground. In keeping with its highly social nature, the Noisy Miner usually feeds in small groups.

The Indian Myna is equally, if not more aggressive in their behaviour. They are known to take over nesting sites, feeding grounds and airways. Attacking, displacing and sometimes killing not only other birds but also small mammals and bats too.

Unlike the Noisy Miner, the Indian Myna are scavengers, residing in urban areas, parks, gardens and streets and will eat almost anything. Surviving well on garbage, scraps, vegetable matter, other bird’s eggs and even eating young hatchlings and small fledgling birds. They follow humans into new suburbs rather than natural variance of vegetation & seasons. Over the past decade, thanks in the main to suburban growth, the Indian Myna has increased its population to such an extent that it became “Australia’s Most Important Pest/Problem”. They have also been nicknamed the “Flying Rats” and due to being introduced to Queensland in 1872 to control the Cane Beetles and Grasshopper, they are often called “The Cane Toad in the Sky”

Another area of difference between the Noisy and Indian is their vocals. Obviously the Noisy by its name is the stronger and superior vocalist of the two. The Noisy has a varied repertoire of communal songs of a 2-3 syllable teu-teu-teu category. Used between them to establish their territory, call alarms to predators and mobbing intruders. This vocal mix starts just before sunrise and will continue to sing, chirp, whistle and chatter through the day. When they want to warn others about possible dangers, their calls become even louder and higher pitched, creating quite a ruckus. While sometimes annoying for us, these guys are great little communicators and can quickly convey important information to the whole group.

By contrast the Indian Myna calls are basic croaks, squawks, chirps, clicks, whistles and 'growls', which are accompanied by fluffs of its feathers and bobs of its head. They also have a loud screech warning when predators are in proximity. In India the Myna are popular as cage birds for their singing and “speaking abilities”. Fortunately, that experience has not been attempted here on their Australia relations.

Even in Breeding there are marked contrasts between Miner and Myna

Noisy Miner breeds communally. Groups include several males and females, and young of previous broods. There are about three males for one female. Males mainly help one another rearing the nestlings. The breeding season is between July and December

Miner’s nests are situated in the forks of trees or shrubs. Females build the cupshaped nest with twigs and grasses. Miners prefers nesting areas surrounded by short grassy spaces, because their young often tend to fall out of the nest too soon after hatching, and this kind of habitat allows adults a better view of predators. Usually, young birds once on the ground spend the time in a bush or low branch, while some family members stand guard to attack any approaching intruders.

The Miner female lays and incubate her eggs alone. Incubation period is around sixteen days. Both sexes care and feed the young, and helpers share these duties with parents. Noisy Miners may produce several broods per season.

In total contrast the Indian Myna are believed to pair for life. They breed through much of the year depending on the location,

The India Myna are known to use the nests of kookaburra, parakeets, etc. and easily take to nest boxes; Nesting material includes twigs, roots, grasses and rubbish. The Myna has been known to use tissue paper, tin foil and sloughed off snake-skin.

It has been recorded that Myna will evict the chicks of previously nesting pairs by holding them in the beak and later sometimes not even using the emptied nest. This aggressive behaviour contributes to its success as an invasive species. The Female will incubate for a period of around eighteen days and both male and female assist in the fledging period of up to twenty-four days.

Although both the Miner and the Myna are relatively common in our neighbourhood, they have yet to start nesting within Sanctuary Lakes Estate itself. But if and when they do, it will be good to know there are actual differences between a Miner and a Myna.

The seasonal cold, wet and windy weather, signals the arrival of Sanctuary Lakes feathered winter visitors. These tend to be birds who normally spend the majority of the year in the higher upland forests and woods, but who often migrate in the winter to urban coastal areas for a stable food supply, safety and security. These visitors tend to separate from their summer breeding flocks and arrive at the Estate in singles or pairs and sometimes even a tiny family group.

These extremely small groupings make it difficult to catch up and meet with some of the visitors, but luckily, I have help from Sanctuary Lakes keen eyed bird aficionados. My first winter visitor “Tip Off” came whilst queuing at the local chemists. Two charming local residents told me that a pair of Currawongs were noisily visiting their gardens, in the gated Jardin community.

Pied Currawong Strepera graculina

Next morning, I slipped into Jardin via the Golf Course and almost immediately I heard the loud cries, croaks and screeching yodel sound, repeating the call “curra…wong” from which the bird gets its name.

The Pied Currawong is an Australian native. A large (50cm), mostly black bird, with a bright yellow eye. Small patches of white are confined to the under tail, the tips and bases of the tail feathers and a small patch towards the tip of each wing. It is often mistakenly confused with the Raven or Magpie. Currawong has nowhere near the number of white patches as a Magpie and has much shorter legs. They are similar in size and plumage to Ravens, but they are slimmer and have much larger and stronger bill. But what makes them readily distinguishable from Magpies and Ravens is their comical flight style in amongst foliage, appearing to almost fall about from branch to branch as if they were inept flyers.

The Jardin bird watchers told me that the Currawong seem to enjoy being a dominant bird that can noisily drive off other species even from their temporary residence.

Pied Currawong hunts mainly in trees and on the ground, searching for a wide variety of food, such as lizards, insects and berries. In the breeding seasons it is known to take chicks from other species nests. In Sanctuary Lakes it feeds comfortably on our large winter supply of berries and small vertebrates.

My second “Tip Off” was from a fellow wanderer who told me at sunrise that morning he had been looking at what he thought was a short stumpy branch of a Eucalyptus Tree when it suddenly grew wings and flew off. I thought that sounds familiar, but it took me five early morning visits to the area before I saw and confirmed that it was indeed that master of camouflage, the Tawny Frogmouth

Tawny Frogmouth Podargus strigoides

Tawny Frogmouths are large birds (40-50 cm) whose plumage is a finely streaked mottled grey and brown. Their wonderfully designed feathers give the Tawny a perfect camouflage and when they stay statue-still on a tree branch, they can appear to be part of the tree itself. They often choose to perch near a broken tree branch and thrust their head at angle, further mimicking a tree branch.

Although Tawny Frogmouths are often referred to as owls, they are not. In fact, they are more closely related to nightjars than owls. But they do resemble owls with their large eyes, soft plumage and camouflage patterns, both owls and Tawnies are mainly nocturnal with both hunting at night.

Unlike owls, Tawny Frogmouths do not have powerful feet and talons with which to capture prey. Instead, they prefer to catch prey with their beaks. Their soft, wide, forward-facing beaks are designed for catching insects. They will also feed on small birds, mammals and reptiles. This larger prey when caught, is held in the bill and beaten against a branch before swallowing. Most of their hunting is done in the first few hours after dusk and just before dawn.

The third “Tip Off “came from a member of the Golfing fraternity who enjoys an early winter sunrise walk around the third and fourth fairways and the linking areas to St Andrews Square. He told me that recently on a couple of occasions he had heard a strong, impressive low and rather mournful sounding double-hoot. Each hoot lasting a few seconds, broken by a brief silence with the second note always being a slightly higher pitch. He said it sounded like an Owl, I think he was correct as the loud two note hooting sound seemed typical of the Powerful Owl.

Powerful Owl Ninox strenua

The Powerful Owl unlike the Tawny Frogmouth is a genuine Australian Native Owl, in fact the largest Owl resident in Australasia with an adult height of over 60cm and an impressive wingspan of 140cm (almost the same length as our social distancing requirements!). Strangely, Powerful’s have a relatively small head, but with hypnotic round yellow eyes, set in a dark grey facial mask. The legs are feathered with massive yellow to orange feet, with large, sharp talons.

The Powerful Owl usually inhabits the moist upland forests of Victoria, but never more than 200klm from the coast. Its main item of prey are small mammals particularly Possums and Bats.

Locally I observed my first Powerful Owl at the Werribee Treatment farm and then last year at the Point Cook homestead. Although over the last couple of weeks I have heard around the Estate the distinctive Powerful Owl call, I have yet to see it physically. Mainly due to the early morning winter sun so far, has not been strong enough to lighten the upper canopy of their favourite Gum Trees. Deakins University who have attached tracking devices to the Powerful Owl are following their movements around Victoria and they confirm that they are visiting our area. One of the unusual discoveries from Deacon’s study is that Powerful Owls in suburban areas enjoy visiting Golf Courses particularly those with fresh water ponds and creeks. I would say Sanctuary Lakes Golf Course fits the Powerful Owls lodging requirements quite adequately.

These three visitors, The Currawong, Frogmouth and the Powerful seemed to have joined the other 90 plus bird species that regularly visit or call our Estate home. Making the point that as our Resort matures, our Birdlife continues to develop and grow, making a pleasurable contribution to all of us who live in the Sanctuary Lakes Estate.

As Resort Maintenance Manager Greg Fryer and Lake and Irrigation Manager Anthony Withington will always tell you, the secret to keeping our Lake absolutely pristine perfect is to maintain a vigorous healthy revolving food chain within the lake. The sea grasses and other our aquatic vegetation, supports the small invertebrates, such as Shrimps, Snails which equally support the fish, who in turn along with the vegetation support the water birds. All in their own way play their part in circulating the food chain and keeping the Lake pristine.

But all this can unravel if the water balance swings away from the desired salinity levels.

And this happened dramatically, over the last twelve months with excessive fresh water flowing into our Lake. Due in part to our changing weather cycle of increased spring and summer rainfall, has meant our roadways and wetlands poured their stormwater into the Lake. This had an immediate effect of increasing Seagrass growth due to the increase in nutrients entering the lake system The 2020 calendar year saw a growth of 863 tons, a 60% increase of Seagrass on the yearly average of 535 tons. Equally dramatically within the Seagrass, the Algae bloomed to the highest amount ever recorded. Putting the Lake in danger of being covered in unsightly, smelly floating mats of Algae. Fortunately, due to constant vigilance and hard work from the Lake Maintenance crew this only occurred in very minor cases. Algae is an essential link in the Lakes food cycle, so why is it perceived as a “baddie”. The predominant Algae in Sanctuary Lakes is the Filamentous algae

Filamentous algae floating on the surface of the Lake

Filamentous algae are colonies of microscopic plants that link together to form threads or mesh-like filaments. These primitive plants normally grow under the water on the leaves of seagrass stems or other substrates, but when over-produced they will break loose, rise to the surface and form floating mats. Filamentous algae are important because they produce oxygen and food for the plants and animals that live in the Lake, but they also can cause problems such as clogs and stagnancy. Filamentous algae do not have roots; rather they get their nutrients directly from the water meaning that their growth and reproduction are entirely dependent on the amount of nutrients in the water. Because our Lake collects stormwater flowing from the wetlands, gardens, golf course and roads within and around our Estate, the abundance of algae is a result of the many sources of nutrients from our residential and local commercial developments.

Filamentous algae do not produce toxins that are harmful to humans. The floating clumps are unsightly, but they are not in themselves a threat to your health. The problem lies when the Filamentous algae grows to the extent that there is an overabundance on the Lake’s surface. This will limit the exchange of oxygen between the water and the atmosphere, and will prevent photosynthesis from producing oxygen in the water. As a result, it is more likely to see fish dying, waterbirds fleeing and an unpleasant noxious odour due to lack of oxygen.

Fortunately, this has not happened and our Lake has never been healthier, just witness the number Water Bird species now visiting the shores. Also there has been an increase in not only species of fish, but actual numbers. The Anglers tell me that Black Bream, Red Mullet and Flatheads are plentiful and they have been joined by a smallish shoal of Australian Salmon and a large number of Short Fined Eels.

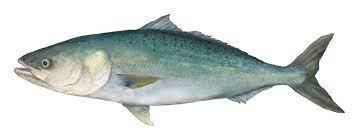

Australian Salmon Arripis trutta

Although it is commonly referred to as a salmon in Australia and its species epithet trutta is the Latin for trout, sadly it is not related to the salmon or trout Salmonidae family. The probable reason for the name is that there is a slight similarity in shape and colour to the Atlantic Salmon. They are streamlined with long slender bodies and have a dark blush green dorsally and silvery white ventrally. The Aussie Salmon’s average size is around forty centimetres and can weigh four to five kilograms. Large shoals are found in Port Phillip Bay and are often seen locally around Altona Pier. Anglers have told me that the Aussie Salmon is a “sporting catch” and not a bad feed, so long as you cook it fresh and it’s great for the BBQ. Unlike the ‘pink’ flesh of the Atlantic Salmon the Australian Salmon has a pleasant white colouring.

The other newcomer to our Lake neighbourhood and is being caught with reasonable regularity by our anglers is the Short-finned Eel

The Short-finned Eel Anguilla australis

Short finned eels have an interesting life-cycle. The mature adults return to the sea in order to spawn. Where they actually spawn is uncertain, but is believed to be in the South Coral Sea off the coast of North Queensland. Mature females about a metre in length have been found to contain more than 3 million eggs. After spawning the Eel will die.

The tiny eel larvae, known as leptocephali because of their leaf like flat shape, are carried south by the East Australian Current from their northern spawning grounds until our Short-Finns reach Port Phillip Bay. At around this time they metamorphose into the normal tubular eel shape although devoid of any pigment and so are known as glass eels.

It is thought that the Sanctuary Lakes Short-Finns have come either through our Tidal Storage Pond on Skeleton Creek or the stormwater retention ponds above Point Cook Road feeding the Canal. Once in our Lake the glass eels quickly develop full pigment, growing to an average size of over a metre in length and weighing approximately one to two kilos. Eels can live for a long time and females have been known to reach the age of 30 years before feeling the urge to migrate into the ocean and begin the cycle all over again.

Anglers rarely deliberately fish for Short Finns, but they can provide good fun catching them. They can also provide good eating.

Thanks to our maintenance Team, this year has once again shown, that our Lake is a magnificent central show piece for our estate.