Tom Parkinson's monthly column, introducing the diverse range of flora and fauna on show at Sanctuary Lakes.

A couple of years back, Martin Hutzebosch found a collection of large fossil bones on the Port Phillip Coastline, south of the Werribee River. After a very thorough study by Melbourne University, the bones confirmed that our corner of Victoria was definitely home and habitat to the Australian Megafauna. Using the latest research I thought it could be interesting to imagine what Sanctuary Lakes looked like and what animals gallivanted around it, 47,000 years ago between the Pleistocene and the Holocene periods.

Sanctuary Lakes lies on the very eastern rim of the Western Victorian Volcanic Plains. These basalt plains were formed by volcanoes over the last 6 million years; basalt which is cooled volcanic lava contains a multitude of large holes which make for natural water springs. Locally we still see them as ponds by Point Cook Village and Jamieson Way. In turn, these springs make the numerous creeks that cover the plains (our Skeleton Creek for example). The plains were vast grasslands, full of unique plant species such as Kangaroo Grass, Spear Grass, Windmill Grass, Tussock and Plume Grass.

Plenty of vegetation and fresh water made the area the perfect territory for Australian Megafauna. There were numerous species of Megafauna at the time but for now, let’s concentrate on four who still have smaller offspring living in Victoria.

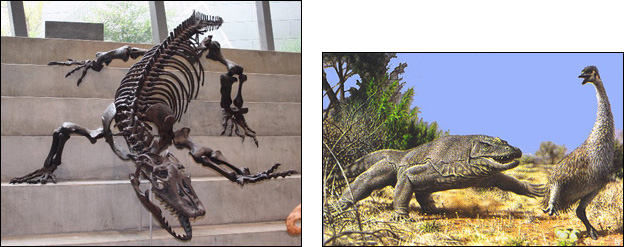

Firstly the closest to a Jurassic monster the Giant Goanna Megalania prisca.

Skeleton in the Melbourne Museum Giant Goanna attacking a Mihirung

Skeleton in the Melbourne Museum Giant Goanna attacking a Mihirung

The Giant Goanna was the largest terrestrial lizard ever known, measuring up to 5 metres in length, with an unusual crest on its snout. The teeth were sharp and recurved with wrinkled, infolded enamel. The Giant had small bones embedded in the skin of the snout and nape of the neck.

Its postcranial skeleton is poorly known, but its proportions were unlike those of other monitor lizards. It was a carnivore. The remains of Giant Goanna’s bones have often been found with broken fossils of large animals like kangaroos, or Mihrung, the Emu’s ancestor. Its size and lack of obvious speed means that the Giant was probably an ambush predator, only running short distances to bring down its prey, then using its toxic saliva which would have caused infection and death to its victims. Being cold blooded it would not have required as much food as a large mammalian carnivore and its large size would have helped even out the fluctuations in temperatures that would trouble the smaller reptile.

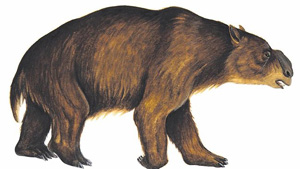

Diprotodon The Diprotodon, meaning "two forward teeth", is the largest known marsupial ever to have lived. Weighing over two tonnes and standing two metres high at the shoulder, the size of a small four wheel drive, they were the largest of the Megafauna. The closest surviving relatives of Diprotodon are the wombats and the koala.

Diprotodon The Diprotodon, meaning "two forward teeth", is the largest known marsupial ever to have lived. Weighing over two tonnes and standing two metres high at the shoulder, the size of a small four wheel drive, they were the largest of the Megafauna. The closest surviving relatives of Diprotodon are the wombats and the koala.

It had pillar-like legs, broad footpads (a little like those of an elephant) and strong claws on its front feet, probably for digging up roots. It was not a particularly handsome animal — its feet were turned inward so it had a pigeon-toed appearance, it had a massive skull and two large upper front teeth. But they were gentle giants relying on their sheer bulk for protection. They are unlikely to have fought violently as their skulls and certain key bones were unusually fragile. They were vegetarians browsing on the shrubs, grasses and trees of the plains. They seemed to be successful as many fossils have worn down teeth, a tell-tale sign of advanced age.

The Diprotodon skeletons show us that one sex (probably male) was considerably larger than the other (probably female). There was therefore a high degree of morphological difference between the sexes. Today in sexually dimorphic mammals, males will mate with multiple females over the breeding season. Diprotodon may also have used such a breeding strategy. They certainly did not wander in herds, but possibly in small family groups lead by the largest male.

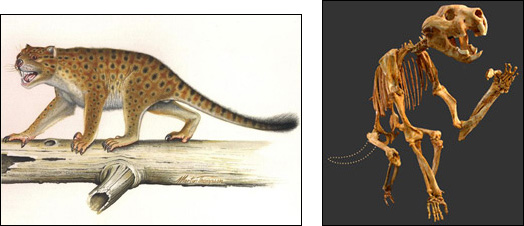

The Marsupial Lion Thylacolea Carnifax is the largest meat-eating mammal known to have ever existed in Australia, and one of the largest marsupial carnivores from anywhere in the world. Individuals ranged up to around 75 cm high at the shoulder and about 150 cm from head to tail. Measurements taken from a number of specimens show they averaged 101 to 130 kg in weight, although individuals as heavy as 164 kg might not have been uncommon. This would make it quite comparable in size to today’s female lions and tigers.

Marsupial Lion (Thylacolea Carnifax)

Marsupial Lion (Thylacolea Carnifax)

The animal was extremely robust with powerfully built jaws and very strong fore limbs. It possessed retractable claws, a unique trait among marsupials. This would have allowed the claws to remain sharp by protecting them from being worn down on hard surfaces. The claws were well-suited to securing prey and for climbing trees. The first digits ("thumbs") on each hand were semi opposable and bore an enlarged claw. Palaeontologists believe this would have been used to grapple its intended prey, as well as providing it with a sure footing on tree trunks and branches. The hind feet had four functional toes, the first digit being much reduced in size, but possessing a roughened pad similar to that of possums, which may have assisted with climbing.

Marsupial Lion might have killed small prey by simply biting their necks, larger prey by biting their trachea just like the African Lion. We can tell by their skeleton they were a running animal and good at climbing trees. Like most mammalian predators they probably hunted in the early hours of dawn and dusk. They would drag their large prey carcass up a tree to feed, removing it from the reach of scavengers, much in the manner of a modern leopard.

Little has been found in the fossil record to give us direct information about the lifestyle of Marsupial Lion. However, three individual’s skeletons shed some light on the raising of young. An adult female with a very young baby ('pouch-young') and a second, older juvenile ('young-at-foot') were all found in association, almost certainly a family group.

For all its vicious and carnivore activity the nearest living relative is the ‘eucalyptus leaf only’ Koala.

A pair of Procoptodons with a joey Procoptodon: the Giant short-faced Kangaroo, the largest known kangaroo that ever existed, stood approximately 2 metres and weighed about 232 kg., living on a diet of leaves from trees and shrubs and distinguished not only by their size but by their flat faces and forward-pointing eyes. On each foot they had a single large toe or claw which might have been used as a defence against marauding predators. On these unusual feet they moved quickly through the open forests and plains, where they sought grass and leaves to eat. Their front paws were equally strange: each front paw had two extra-long fingers with large claws. It is possible that they were used to grab branches, bringing leaves within eating distance.

A pair of Procoptodons with a joey Procoptodon: the Giant short-faced Kangaroo, the largest known kangaroo that ever existed, stood approximately 2 metres and weighed about 232 kg., living on a diet of leaves from trees and shrubs and distinguished not only by their size but by their flat faces and forward-pointing eyes. On each foot they had a single large toe or claw which might have been used as a defence against marauding predators. On these unusual feet they moved quickly through the open forests and plains, where they sought grass and leaves to eat. Their front paws were equally strange: each front paw had two extra-long fingers with large claws. It is possible that they were used to grab branches, bringing leaves within eating distance.

Beside woodland and savannah plains Procoptodons seem also to be at home in harsher environments, vast areas of treeless plains, wind-blown sand dunes and salt marshes. Seems a natural for an early Sanctuary Lakes. Like all marsupials, Procoptodon would have had tiny, hairless young that developed to maturity in a pouch after birth. From skeletal remains it appears they might have lived in small mobs, in a similar manner to today’s Kangaroos.

Extinction: How did the Megafauna disappear? A question that has puzzled naturalist since the first skeletal remains were found. Humans arrived on the Australian continent around 60-70,000 BC and certainly hunted the Megafauna. There are numerous skeletons with evidence of spear wounds. But the vast number of Megafauna compared with the small number of humans would not support this theory. Fire was, as now, a natural event, but humans also used fire for their own needs. Again this is a vast continent and fire as extinction does not add up as the catastrophe. It is known that over a period of 5-10,000 years between the cusp of the Pleistocene and Holocene ages there was a climate change and the Australian continent moved a couple of hundred kilometres north, but again not the events that could remove such a vast and varied number of specific fauna. Possibly over time all four were to blame.

Sadly the outcome meant that by as late as 15,000 BC the Megafauna disappeared completely, leaving their offspring who are probably better adapted to living in today’s climate and with us Humans.

We live now in a zoologically impoverished world

from which all the hugest and fiercest and

strangest forms have recently disappeared

- Alfred Russell Wallace (1876)